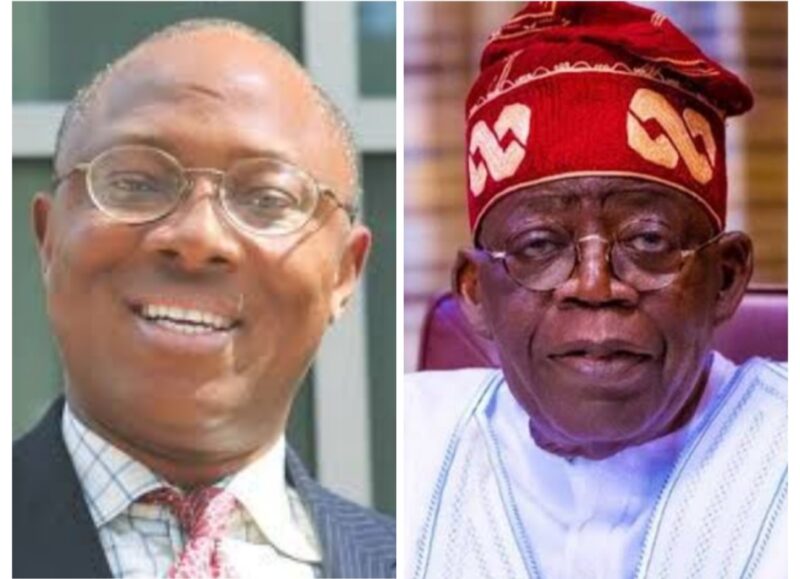

US-based Nigerian scholar, Professor Nimi Wariboko, has urged the Bola Tinubu administration to stop asking Nigerians to endure economic hardship without presenting credible, time-bound alternatives and shared sacrifices from the ruling elite.

Speaking during an interview on Inside Sources with Laolu Akande on Channels Television on Friday, Wariboko, who is the Walter G. Muelder Professor of Social Ethics at Boston University, criticized the Federal Government’s approach to economic reforms, which he described as a “TINA” policy—“There Is No Alternative.”

“And that should be the debate, right?” Wariboko said. “But they are taking this policy of what I call TINA: there is no alternative. I see the policy package they have as the only way to go. It’s not open to debate. But there are always alternatives. We can ask: how do we minimize costs and gain wealth with better timing so we reach the same place with less pain?”

The professor warned that it is not enough for the government to ask citizens to make sacrifices without demonstrating that political leaders are also making visible and measurable sacrifices.

“If you are asking us to bear pain as citizens, is the ruling class and the politicians—are they bearing pain? Because if they are, and visibly, and we can see they’ve cut down the cost of corruption, they are getting less from the government, and they are bearing the pain, then we all know we are in this thing together,” he emphasized.

Wariboko noted that all economic policies have winners and losers, but for the latter group to endure hardship, they must believe that better days are not only coming but are close enough to matter. He expressed concern that Nigerians have been told for decades that the country is “turning the corner,” yet the reality remains unchanged for the majority.

“Anytime you make an economic policy, there are going to be gainers and losers. So you can tell the losers, bear the suffering now, you’ll eventually be compensated. But the question is: do they even know how long that wait will be? Because people forget that at the time of American independence in 1776, Argentina and Brazil were better economies. But they’ve lived in perpetual hope of becoming great. They are not,” he argued.

“So the timing is not there,” he continued. “The way to assess the timing is whether people really feel we are turning the corner. When a society is heavily focused on the present—on just surviving—people will not believe any long-term promises.”

Wariboko raised a fundamental ethical question about the cost of reforms, warning that some of the sacrifices Nigerians are being asked to make are not only difficult but, for many, life-threatening.

“Yes, there is a cost, but there are certain costs that are unbearable. If you’re going to ask your people to bear a certain cost, ask: is the cost going to kill them? If I’m given medicine for malaria and it’s bitter, I can manage. But if the bitterness is going to kill me, then it’s not worth it.”

“People are dying of this suffering,” he said pointedly. “To what extent are we willing to let people die and suffer just to stick to a single policy path? Isn’t there a better mix of policies that could take us where we want to go?”

The scholar’s remarks come amid widespread dissatisfaction over the effects of Tinubu’s economic reforms, including the removal of fuel subsidies and the unification of the exchange rate. While the government insists these policies are necessary for long-term stability and growth, many Nigerians continue to grapple with soaring inflation, food insecurity, and stagnant wages.

Wariboko’s intervention adds to growing calls from economists, civil society, and ordinary citizens for the administration to recalibrate its economic approach—by including broad-based consultation, introducing immediate palliatives, and ensuring that politicians lead by example in cost-cutting and accountability.

“Nigerians don’t have unlimited time,” Wariboko warned. “They need to see that the sacrifice they are making is matched by leadership, fairness, and a real hope they can believe in—now, not in 100 years.”